Chinese Bombers Near Alaska: Signal or Triad Test

A New Phase in Sino-Russian Bomber Patrols

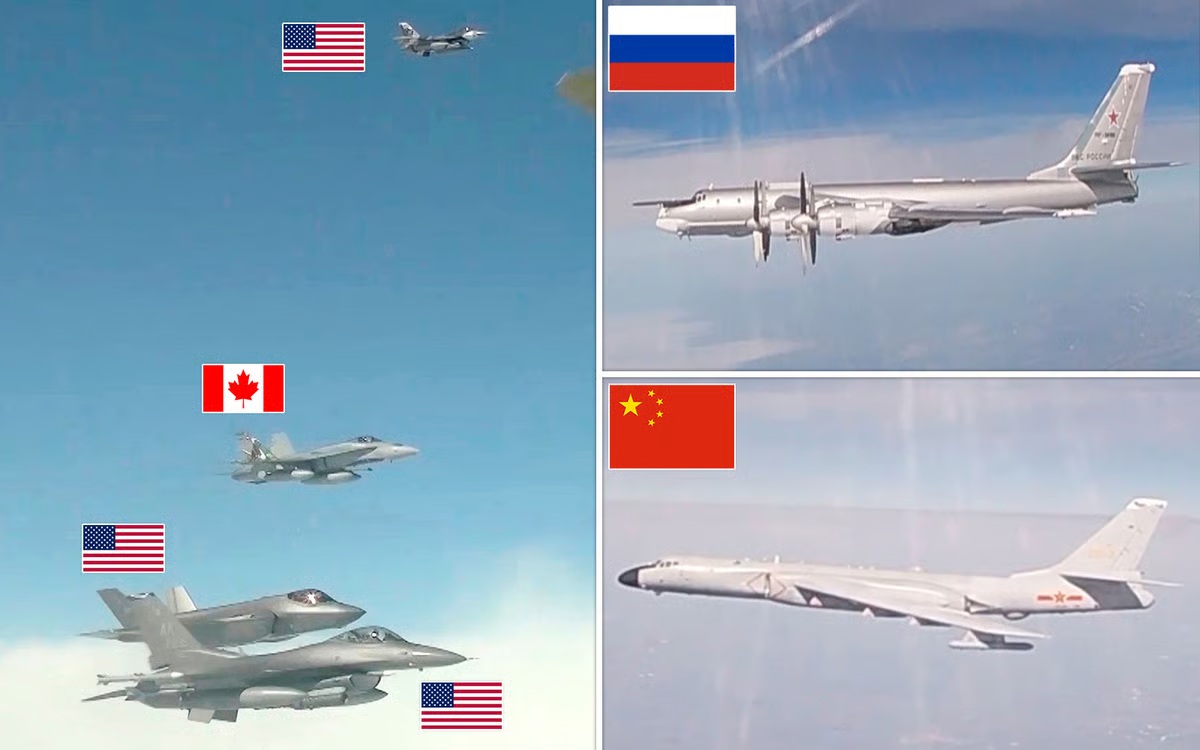

Deploying military forces remains one of the clearest ways to send a political message, and few moves are more potent than placing nuclear weapons or delivery platforms near an adversary. In July 2024, nuclear-capable Chinese bombers joined Russian aircraft on joint patrols near Alaska—the first time such a maneuver had involved the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF).

For military analysts, the move raised immediate questions: was the objective a warning over Taiwan, a deterrent to NATO involvement in Asia, or a statement that the Pacific Ocean is no longer a secure buffer for the United States?

However, new analysis suggests these bomber flights may have had another, more technical motive—the operational integration of nuclear bombers into China’s strategic triad, alongside intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and ballistic missile submarines.

Completing China’s Nuclear Triad

According to Derek Solen, a researcher with the U.S. Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute, these operations fit into a years-long plan to make nuclear bombers a fully functional component of China’s deterrence posture. Solen argued in a report for the Japan Air Self-Defense Force’s Air and Space Studies Institute that the Alaska mission was a demonstration of capability rather than just a political gesture.

Another possibility is that the patrols acted as a warning against U.S. “nuclear sharing” in Asia—the potential deployment of American nuclear weapons to non-nuclear allies such as Japan and South Korea. Beijing reportedly fears this could merge America’s European and Asian alliance systems into a single, nuclear-armed coalition designed to counter China.

NORAD Interceptions and Historic Firsts

The July 2024 patrol triggered immediate responses from the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), which scrambled U.S. and Canadian fighters to intercept the aircraft after they entered the Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) near Alaska.

Significantly, this was the first time PLAAF bombers in a joint patrol had launched from a foreign airbase and approached U.S. territory. Until then, Sino-Russian bomber operations had been limited to the Sea of Japan and East China Sea. The shift to operating near Alaska was a marked escalation in operational reach.

Expanding Capabilities with the H-6N

Days after the Alaska sortie, joint patrols continued over the Sea of Japan, East China Sea, and into the Western Pacific. This time, they included the PLAAF’s advanced H-6N bombers from the 106th Brigade in Henan province—a unit primarily tasked with nuclear strike missions.

The H-6N boasts a range of 3,700 miles and can deploy KD-21 air-launched cruise missiles with an estimated range of up to 1,300 miles. On 30 November 2024, a patrol brought these bombers within cruise missile range of Guam—a move Solen described as possibly the first realistic training for an air-delivered nuclear strike on the island.

Political Timing and Strategic Consistency

Solen initially believed these flights were political messages. They came after the July 2024 NATO summit, which condemned China for supporting Russia’s war in Ukraine and hinted at expanding NATO’s focus on Asia. However, the significant gap between the summit and the November Guam flight suggested a deeper operational agenda.

He noted that the PLAAF officially adopted the H-6N in 2019, the same year the 106th Brigade’s base renovations were completed and Sino-Russian combined patrols began. The timing reinforces the idea that the patrols were part of a structured program to train long-range nuclear strike capabilities.

Military Training or Political Posturing?

While some missions may have dual purposes, Solen argued that purely military training would likely have remained within East Asian waters. The Alaska patrol’s long-range element suggests deliberate planning to test bomber endurance, interoperability, and navigation for extended missions—essential for both nuclear and conventional strike roles.

The Chinese government has consistently opposed nuclear sharing, calling on “relevant countries to abolish the arrangement, withdraw the large number of nuclear weapons deployed in Europe, and refrain from replicating such arrangements in the Asia-Pacific.” This rhetoric aligns with the possibility that bomber patrols are just as much about signalling policy positions as they are about building operational readiness.

The Outlook for Future Patrols

For now, no further joint flights have been conducted in 2025, a decision Solen attributes to political caution during China’s negotiations with the Trump administration over trade disputes. He concluded that regular flights near U.S. territory are unlikely in the short term due to the high cost of training.

However, once political conditions change—whether through resolution or deadlock—combined bomber patrols may resume, and China could conduct long-range solo patrols without Russian participation. Even in non-nuclear roles, such as anti-ship or base-strike missions, these flights provide valuable experience for PLAAF crews.