ISWAP Attacks Military Installations in Lake Chad Nigeria

Rising Wave of Attacks

ISWAP has stepped up its campaign of violence in the Lake Chad area, unleashing a relentless and sustained campaign against military outposts in an attempt to stabilise troubled areas. A minimum of 15 border regions have, this year alone, been targeted by ISWAP, showing the scale of the threat, the Institute for Security Studies reports.

The leading keyword “ISWAP attacks target military installations in the Lake Chad region” indicates the increasing frequency and intensity of the activities, which increasingly undermine Nigerian and regional counter-insurgency operations. Originally built to facilitate the safe return of people displaced by the conflict, these installations are now at the centre of a deadly struggle for dominance.

Tactical Evolution of ISWAP

Boko Haram offshoot ISWAP has increasingly developed its battlefield tactics. In its operation known as Camp Holocaust, combatants have moved from pickups and ad hoc armoured carriers to motorbikes, which facilitate quick raids.

One of these attacks was in May when ISWAP militants on motorbikes raided a Nigerian Army supercamp at Buni Gari, Yobe State, and killed four soldiers. The attack demonstrated how ISWAP attacks focus on targeting military installations in the Lake Chad area by leveraging mobility, overrunning defences, and withdrawing quickly before reinforcements arrive.

“Supercamps” were meant to concentrate Nigerian troops into fewer, more efficient bases with quick response times. But as analyst Jacob Zenn noted, ISWAP’s motorbike strategy enables it to attack quickly and evade decisive confrontation, a trend capable of breaking the stalemate.

Sophisticated Military Operations and Nighttime Strikes

ISWAP has increased the sophistication of its operations by employing commercial drones to conduct surveillance and night bombing. The fighters also isolate outposts by blowing up roads and bridges in the area, cutting off reinforcement and supply routes.

Early in May, ISWAP took over the 50 Task Force Battalion in New Marte, Borno State. Militants absconded with ammunition, abducted soldiers, and stole at least 45 vehicles. The group attacked bases in Dikwa, Rann, and New Marte simultaneously and interdicted the vital Damboa-Maiduguri corridor within days.

This wave of attacks resulted in large-scale displacement of civilians and showed how ISWAP attacks targeted military camps in the Lake Chad area by conducting coordinated attacks on both civilian and military supply lines.

Structural Imperfections of Nigerian Military

Military reinforcements come too late, and weak infrastructure and prolonged resources exacerbate vulnerabilities. ISWAP attacked the 149 Battalion garrison at Malam Fatori on the Niger border in January. The fighting raged for three hours and killed at least 20 soldiers, including the commander. Witnesses said no reinforcements or air support came, and ISWAP was able to ransack the base of arms.

Institute analyst Taiwo Adebayo contended that merely establishing far-flung camps is not enough. Rather, Nigeria should locate bases in proximity, increase mobility, and commit enough troops and equipment. Lacking structural reform, ISWAP raids on Nigerian Army outposts in the Lake Chad region will continue to expose the Nigerian Army’s lack of operational depth.

Geography as an Insurgent Resource

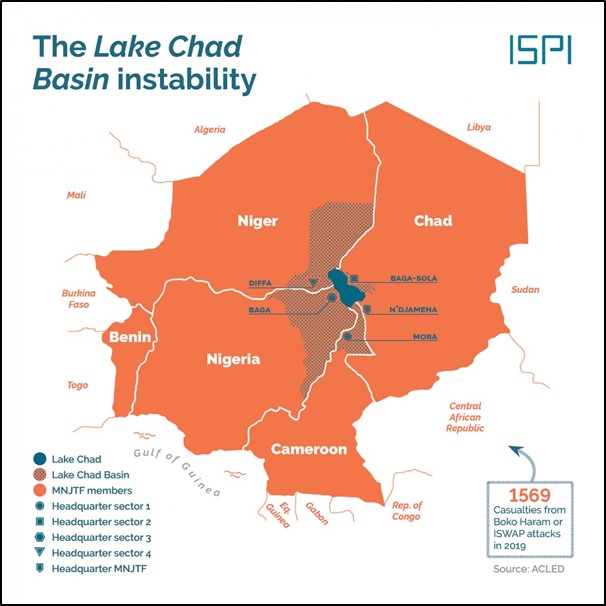

The vast wetlands, islands, and porous borders of Lake Chad provide ISWAP with a certain level of cover and mobility. The Chad, Niger, Cameroon, and Nigerian governments have ceded large parts of this terrain, creating areas of operation. Adebayo recommended increasing amphibious capabilities and leveraging the naval capacities of the Multinational Joint Task Force to attack the command hubs of ISWAP.

The above environmental conditions show the challenge in fighting ISWAP attacks on military installations in the Lake Chad area, where the terrain significantly enhances the insurgents’ strategic advantage.

External Training and Support

ISWAP, according to new defectors, receives support from at least six Islamic State trainers dispatched from the Middle East. Their deployment has furthered the group’s tactical skills and helped professionalise their forces. This foreign influence highlights the transnational nature of the conflict and the strategic role of the Lake Chad Basin in IS’s wider global campaign.

ISWAP’s Finance and Governance

Apart from its military activities, ISWAP also claimed to have a “caliphate” in northeastern Nigeria and Lake Chad. ISWAP also has taxation, justice, religious enforcement, and public welfare departments, senior researcher Malik Samuel explained.

By taxing fishermen and cattle herders on Lake Chad islands, ISWAP earns an estimated $191 million a year — a decade more than the Borno State government. Such financial autonomy consolidates the group’s power and explains why ISWAP attacks on the military outposts in the Lake Chad region are not just military operations but are a part of a grand agenda of state-building.

Conclusion

ISWAP’s sustained campaign illustrates how insurgents leverage mobility, sophisticated attacks, and governance to compete with conventional militaries. Its use of motorcycles, drones, and local taxes illustrates that an organisation is adapting to change more quickly than the states that are fighting it.

Unless Nigeria and regional partners reorient their defense stance, acquire amphibious capability, and provide speed mobility, ISWAP military raids on bases in the Lake Chad region will persist. The war is not now about holding territory in itself but about testing state legitimacy and extending governance where the state has not.