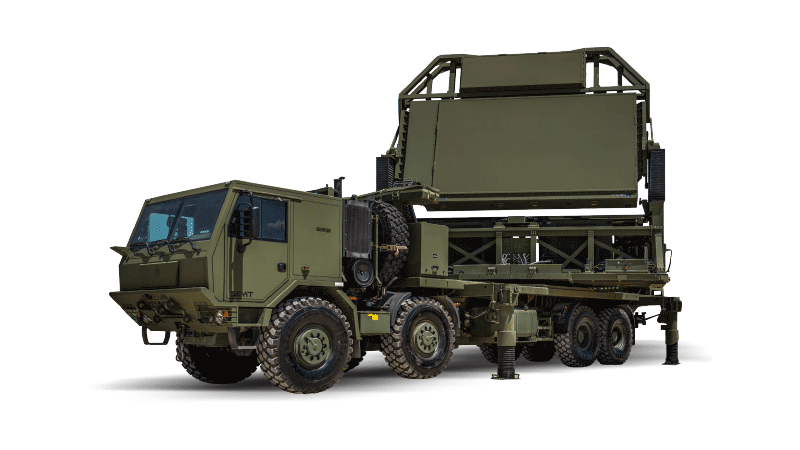

Türkiye’s ALP-300G Radar

Why does this matter now?

Türkiye’s ALP-300G radar has ignited debate by reportedly detecting stealthy F-35s at up to 650 kilometres. If accurate, the capability shifts assumptions about survivability in the Eastern Mediterranean’s crowded airspace. Moreover, it signals Ankara’s growing confidence in indigenous sensing and integrated air defence.

A sovereign counter-stealth play

After its 2019 exit from the F-35 program, Ankara doubled down on its native systems. The ALP-300G radar sits at the heart of that push. It aims to deliver wide-area early warning, resilient tracking, and cueing for layered SAM networks. Consequently, the system strengthens Türkiye’s autonomy and messaging toward its neighbours and NATO peers.

Designed for low-observable threats

Operating in the S-band, the ALP-300G radar exploits longer wavelengths. These frequencies reduce the effectiveness of stealth shaping and RAM at long range. As a result, the radar stands a better chance of initially detecting low-RCS aircraft such as the F-35 Lightning II.

AESA at scale

An AESA front end, built from thousands of transmit-receive modules, enables agile beam steering and high update rates. Therefore, the ALP-300G radar can search large volumes fast, manage dense target sets, and adapt waveforms on the fly. Distributed TRMs also provide graceful degradation in the event of kinetic damage or jamming.

Mobility and survivability

Mounted on 4×4 or 8×8 vehicles, the ALP-300G radar can displace after radiating. That mobility complicates pre-emptive strikes and keeps coverage flexible across fronts. In turn, commanders can reposition sensors to watch the Aegean, the Black Sea, or the Levant with minimal downtime.

The 650 km claim in context

Turkish strategist Dr Eray Güçlüer has asserted that the ALP-300G radar can detect an F-35 at 650 km and see “every object up to 750 km.” Under ideal conditions, such performances are more plausible: high-altitude targets, a clear line of sight, minimal clutter, and favourable atmospheric conditions. Even so, intermittent or coarse detection at very long range still matters, as it buys commanders time and options.

From first contact to fire control

Early detection is only the first step. Typically, track-quality data arrives at shorter ranges or via multi-sensor fusion. Nonetheless, “first contact” at range lets the ALP-300G radar cue other sensors. In practice, it can tip off L- or X-band radars, ESM receivers, or IR systems to refine the track. Thus, the network edges closer to an intercept-quality solution.

Networked IADS effects

Integrated with HERİKKS-600 C2, the ALP-300G radar feeds a common operational picture. Consequently, it can cue HİSAR-O, HİSAR-U, or SİPER batteries and coordinate with fighter CAPs. While the initial look may be rough, the network restricts the stealthy aircraft’s freedom to manoeuvre, especially near defended coastlines.

Technology drivers behind the claim

Three advances underpin the ALP-300G radar story:

- GaN power.

- Digital Beamforming.

- Software-defined agility.

GaN power and aperture

Gallium-nitride TRMs push higher power density and thermal margins. As a result, the ALP-300G radar can extend detection ranges and sharpen ECCM performance. In counter-stealth roles, more radiated energy and cleaner sidelobe control improve the odds of a hit on small RCS targets.

Digital beamforming and agility

With digital beamforming, the radar can form multiple beams, adapt dwell times, and switch PRFs intelligently. Therefore, the ALP-300G radar varies look angles and waveforms to frustrate jammers and reduce predictability. Additionally, adaptive scheduling helps separate slow, low flyers from clutter along the littorals.

Low probability of intercept (LPI)

Stealth missions rely on surprise. However, LPI techniques reduce the radar’s signature to hostile RWRs and ESM. Consequently, the ALP-300G radar can search wider sectors for longer without advertising its exact location. Combined with mobility, this complicates suppression planning.

How it stacks up against peers

Counter-stealth surveillance is a global race. Russia’s Nebo-M and China’s JY-27A/JY-27V offer relevant benchmarks. Open sources report that the Nebo-M can detect flying objects from over 600 kilometres away, while the JY-27 family can detect stealthy aircraft from several hundred. In that light, Türkiye’s ALP-300G radar claim sits within a competitive envelope—especially for first detection rather than continuous fire-control tracking.

Operational realities and caveats

Claims asking for scrutiny of terrain masking, atmospheric ducting, and sea clutter can all degrade performance. Furthermore, mission profiles matter. Low-altitude ingress, emission control, and cooperative jamming can cut detection range significantly. Even then, long-range cues from the ALP-300G radar still change the calculus by reducing surprise and compressing decision timelines.

Psychological and deterrence effects

Perception shapes planning. If crews believe the ALP-300G radar can “see” them hundreds of kilometres out, they will alter routes, altitudes, and refuelling plans. The result is fewer options and narrower timing windows. Over time, that perceived visibility exerts a deterrent effect even when physics limits perfect tracking.

Strategic implications for the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a sensor-rich, fast-moving theatre. Greece and Italy field F-35s. Israel flies F-35I Adirs. Russia operates advanced SAMs and sensors from Syria. In this situation, a mobile ALP-300G radar that uses S-band technology can detect and guide an Integrated Air Defence System (IADS), increasing the danger. Therefore, planners must account for earlier detection, faster cueing, and tighter engagement timelines.

Procurement and doctrine ripple effects

If counter-stealth detection continues to improve, air forces will invest more in EW, decoys, and stand-off weapons. Simultaneously, they will refresh LPI tactics, embrace multi-spectral deception, and lean on distributed missions. Conversely, air defence operators will add multi-band fusion and passive sensors to capitalise on long-range cues from systems like the ALP-300G radar.

Bottom line

The ALP-300G radar claim of 650 km F-35 detection is ambitious yet directionally consistent with modern counter-stealth trends. In ideal conditions, long-range first detection is credible. Even without fire control precision at those distances, an early cue can tip a network defence. As a result, the balance of risk in the Eastern Mediterranean nudges toward the defender—exactly the strategic message Ankara appears to intend.